As we try to handle ever more complexity and uncertainty in our lives, co-creative skills are essential. Co-creativity is about both-and, combining action and reflection, balancing your needs and aims with the realities of the situation and other people in it.

One way of developing co-creativity is through the left and right sides of the brain. Roger Sperry, an American psychologist, won the Nobel Prize for medicine in 1981 for his research on the left and right hemispheres of the human brain. The talents of the left side include logic and reasoning: the ability to analyse a complex situation, to identify chains of cause and effect.

The right side of the brain offers such gifts as intuition and imagination: it is more visual, spatial, and conceptual. While the left brain can dissect a complex situation, break it into smaller parts by analysis, it is the right side that gives us synthesis, creative vision, the fresh combination of parts to move us forward. Most people habitually use one side of the brain – more than the other.

Try consciously to use both sides. I have a quick analytical mind, so I frequently need to slow myself down. If you’re more naturally intuitive, try asking yourself logical questions.

This may sound like hard work, but it soon gets easy with practice. One of my favourite ways to use the whole brain is what I call Park and Ride. I start by thinking analytically about a problem, I gather facts, questions, puzzles. Then I stop fretting: I park the problem, do something else, and usually my intuition pops up with an answer.

Linda and I are constantly combining analysis and intuition in our gardening: for example if a new problem arises like rust on the onions, or peach leaf curl. Our first steps are usually logical, gathering facts from garden books or websites. Intuition comes in when we decide if this is serious enough to intervene, or if the plants can cope with it. And we’re also using intuition to look for a ‘systemic’ solution, like a need for more crop rotation, or a change to our composting methods.

The Diamond Process

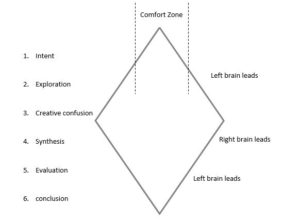

The Diamond Process offers a route map for the co-creative approach, and a framework for using both sides of the brain. I developed this process as a way of teaching managers how to handle high levels of change and uncertainty. It is relevant for issues of many kinds, including practical, big- picture, or emotional. It can be applied quickly or in depth.

The shape of the diamond symbolises the shape of most change processes. There is a starting point: an intention, a question, a partial understanding of the situation. From this point, the picture widens into growing uncertainty, confusion, and contradiction. A successful change process then finds new insight that gives clarity and focus, bringing the process to a finishing point, which in turn will typically be the start of another diamond.

Comfort zone

The six stages in the process are as follows.

1. Intent

You plant the seed for this process by stating and affirming your intent. Even if your aim is as vague as “to understand my confusion”, it helps to state this explicitly. Feeling your tension and affirming your desire to reach an outcome raise your energy and motivation for the process. Another benefit of doing all this is that it engages your intuition in the process. The same approach is expounded by Timothy Gallwey in The Inner Game of Tennis: the logical brain specifies the goal, but never prescribes how to achieve it. It briefs the intuitive mind to find the solution.

2. Exploration

In each phase of the Diamond Process, both sides of the brain contribute but one takes the lead. Here it is the active, logical, left brain. This is the stage for gathering data, exploring a range of information sources, analysing what’s going on, looking for relevant parallels, and so on. One aim of the exploration phase is to go beyond your comfort zone: the habitual frame of reference and limiting beliefs that we use to reduce the confusions of real life to a manageable level.

3. Creative Confusion

If your exploratory work has been done well, it will naturally propel you into confusion. Real life is full of changeability and contradiction, to an extent that can be almost intolerable. As TS Eliot said, “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.” The word confusion literally means a flowing together,

and the aim in this stage is to relax into the tension and uncertainty: to feel its intensity and to stay with it. This stage is the transition to leadership by the right brain, the receptive principle.

4. Synthesis

This is the phase when you open receptively to the “aha!” moment, the creative insight that produces a way forward from the creative confusion. Like any right-brain process, you can’t force it. There is a saying, “In sleep, sex and fishing, the more you try, the less happens.” The same applies here. Sometimes just closing your eyes, breathing peacefully, and waiting enables you to find the synergy. If not, this is a good time to go for a walk, have a bath, sit in the garden, play some music: do something enjoyable and stay observant for the answer when it’s ready.

5. Evaluation

This is where the left brain takes the lead again. You have a vision of an outcome: it may seem sensible or it may seem crazy. Either way, you need to check out the practicalities, do the sums, ask the questions. None of us have 100% infallible intuition, and you may have to return to an earlier phase of the cycle to check things out.

6. Conclusion

Your evaluation may support your new vision, or highlight doubts or risks. Before you go ahead, return to the right brain: sit with your potential decision, see it in perspective, ask if it inspires and motivates you. This is the stage where we often say: “I’ll sleep on it”.

It is sometimes wise to cycle back within this process and repeat some stages. For example, the creative confusion stage may raise more questions to explore. Or you may alternate for a while between confusion and synthesis. It’s also cyclical because the conclusion to one diamond often becomes the starting point for another.