A different approach to future happiness

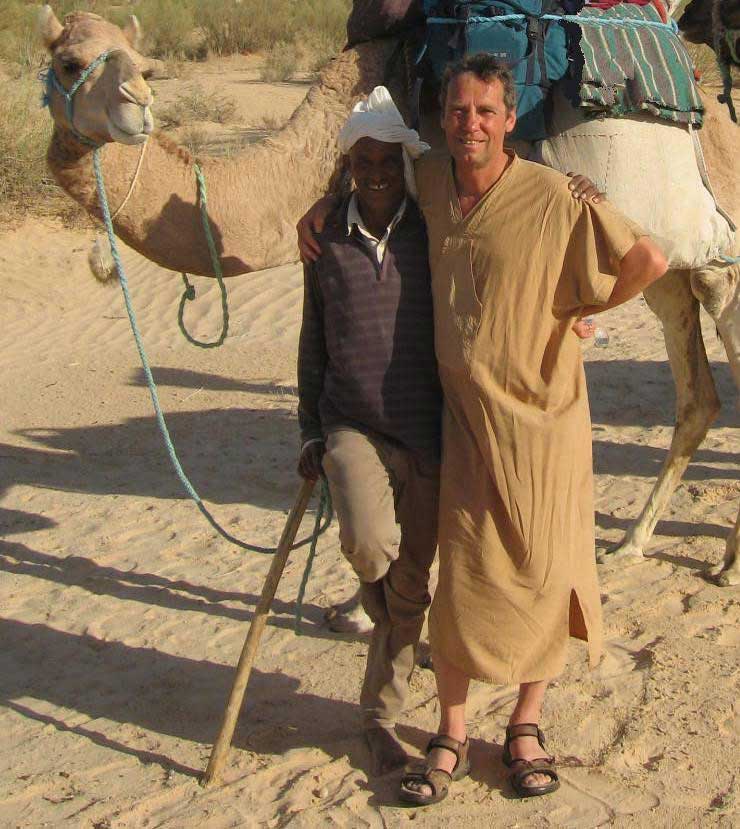

One of my big life-changing experiences was co-leading a dozen retreats in the Tunisian Sahara with Bedouin guides. They had grown up as true nomads, moving around the desert with their camels and goats, but now living mostly in a town because many desert wells had dried up.

Our Bedouin guides had few material resources, little control over their situation, yet were living happily with huge levels of uncertainty. I regard them, and nomads generally, as a really valuable lead indicator for all of us, as we face rising disruption and less control on many fronts. So here are my pointers to what we can learn from the nomad way of living.

- Roots in the land: whilst owning and cultivating land is not part of the nomadic way, they are deeply familiar with huge tracts of land which they roam across, so they know where the resources are. The parallel for us is to have a wide-ranging awareness of where we could find support, both practical and emotional: see more below.

- More tribal, less individual: for nomads, the tribe is crucial, as a source of identity, stability, mutual support, when so much is fluid. Some wise observers (like Neil Douglas-Klotz in his book Desert Wisdom) believe that ‘developed’ societies overemphasise individual identity and needs, with a loss of collective wisdom and capacity. It’s clearly hard for us in these societies to regain the strength of tribal spirit which nomads still have, but we can lean towards it: this is one of many reasons why local communities are so important.

- Simple, shared resources: here’s an example. Our Bedouin guides used their warm camelhair burnous (cloak) to do four jobs that the visitors needed four different bits of kit for: evening garment as the nights got chilly, sleeping mat, sleeping bag, and saddle pad for riding camels. We could also see that the Western fixation with private, personal possessions didn’t apply: most resources were seen as collective.

- Life as a unity: as we trekked through the dunes, the Bedouin would sing as they led their camels. I’d ask the meaning of each song, and soon realised they constantly interweave love songs, chants about the desert, kids’ songs, and praise to Allah. For them, all life was one unity: you couldn’t separate work and play, or sacred and earthly, it was one vibrant flow.

- Adapt to circumstances: this could be a definition of nomadic life. You move to where the water or the grazing is. In a severe drought, you slaughter some of your stock, and hope to get through it. My desert trips kept reminding me of what high expectations I have about my comfort, and how shallow my survival skills are.

- Keeping faith: the Bedouin I travelled with were Moslems who prayed to Mecca, and also kept their own faith in the spirits of the desert. Their beliefs flowed through every moment of their lives: a trust in divine unity, a power in all life which was bigger than human understanding. Before each meal, as a grace, the visitors and the Bedouin would sing together, Bismillah er-rahman er-rahim: we begin in the name of divine unity, who is mercy and compassion.

Although in countries like Britain we are in a much more fragmented, individualistic society, there are many qualities of nomadic life which we can adapt and share as times keep getting more uncertain.

For more about Alan’s desert journeys, including a short video, see www.living-organically.com.