Probably… and how can we prepare?

By food emergency, I mean a prolonged period of serious food shortages, and/or extreme food price inflation. Many of us already know how fragile Britain’s food security is, and how flimsy the long-standing Government strategy is: ‘Leave it to Tesco.’ We currently import 46% of our food, and supply chains are complex and vulnerable. Is an outright food emergency a serious risk?

The best expert I know in this field is Tim Lang, Professor of Food Policy at City University, and author of Feeding Britain. Tim believes there is a high risk of outright food shortages in the UK within the next few years, and I am delighted that he is working with the Welsh Government and other organisations here on responses. Let’s look at some of the reasons this emergency could be happening:

- Multi-breadbasket failure: This issue has been highlighted by many experts, including Jem Bendell: this is the risk of simultaneous crop failures in the small number of global producers for a range of major staples such as wheat, rice, soya, etc.

- Mediterranean basin: the great majority of Britain’s fresh fruit, seafoods and veg come from this area, with Spain and Morocco especially important. We’ve already seen some supply shortages in UK supermarkets, due to extreme heat and drought. It’s forecast that production from the whole Mediterranean basin will halve by 2050 due to reducing rainfall.

- Supply chain failures: the chain contains only a few days’ supply, and could fail in so many ways. I’m increasingly concerned about the internet going down, as explored in the UK Future Risks Review which I recently commissioned. Possible causes include cybersecurity and solar flares. Professor Lang also highlighted the internet and IT systems as a weak spot. In recent years we’ve seen brief supply breakdowns, e.g. due to Brexit, and there’s really no quick remedy when they happen.

So is anyone aware of these risks and preparing for them? The UK Government maintains a National Risk Register, and strikingly, only one of the many risks it assesses relates to food, and that’s about bacterial infection, not supply. Tim Lang is currently writing a major report on food security for a body I’d never heard of, the UK’s National Preparedness Commission. It’s due for publication in May 2024.

In the part of Wales where I live, Powys, we are fortunate to have a dynamic food security project for the bioregion, Our Food 1200, who also believe that a food emergency is likely within the next few years: they are working with Tim Lang and the Welsh Government to improve resilience and food sovereignty, hoping that Wales can be a lead indicator for the UK.

On April 16, Tim Lang was the keynote speaker at a conference convened by the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, with an excellent turnout from all relevant sectors in Wales, including the NFU. There is all-party support in the Welsh Senedd to treat this issue as urgent, recognising that Wales has substantial food poverty, poor diet and related health issues, and currently even higher import dependence than the UK generally. The Welsh Government, with help from Our Food 1200, are now starting the process of more detailed briefing and consultation with all relevant sectors in Wales to evolve a response plan.

Recently, one of my contacts attended a conference on food security, where a main speaker was a representative of Tesco. She forcefully endorsed concerns about a food emergency, and said that Tesco already have a team of 50 people working on the issue. Does that worry or reassure you? We can assume that Tesco’s motive is not our wellbeing, but their profits, and my guess is that they are taking out forward supply contracts, which means that smaller retailers simply won’t have stocks when shortages hit. So this underlines the urgency of national and local governments, and local communities, making their own preparations.

So what could we do at household or local community level? The answer is plenty, but I am painfully aware that most of us are overstretched by daily life and the many other threats that we’re either fretting about or trying to ignore. Professor Lang’s report will probably focus on national strategy, and I’d really like to know if there’s any well-considered guidance out there for the grassroots. Meanwhile, here are my initial thoughts:

Prepping: don’t be deterred by the lunatic fringe, it’s a basically sound idea. Every household should have a few weeks’ survival store of dried, tinned and frozen food.

Soup kitchens: I have a recurring vision of Britain eating from communal soup kitchens sometime in the next few years. There could be benefits, for example rebuilding community connections. Communal catering is a very efficient, equitable way of using scarce food resources. Do we have enough community kitchens to meet the need?

Local growing: it’s exciting to see the growth in local food projects such as Community Supported Agriculture, but… clearly the scale of these is small in relation to national demand, and most of them understandably focus on vegetables and salad crops. A food emergency may well mean shortages of proteins and carbohydrates, which are generally farm-scale products. It would be great if food growing projects could expand in scale and include potatoes, pulses, etc., and at least where I now live in Wales there’s a prospect of this approach being taken seriously and supported by the Welsh Government and regional bodies like Our Food 1200.

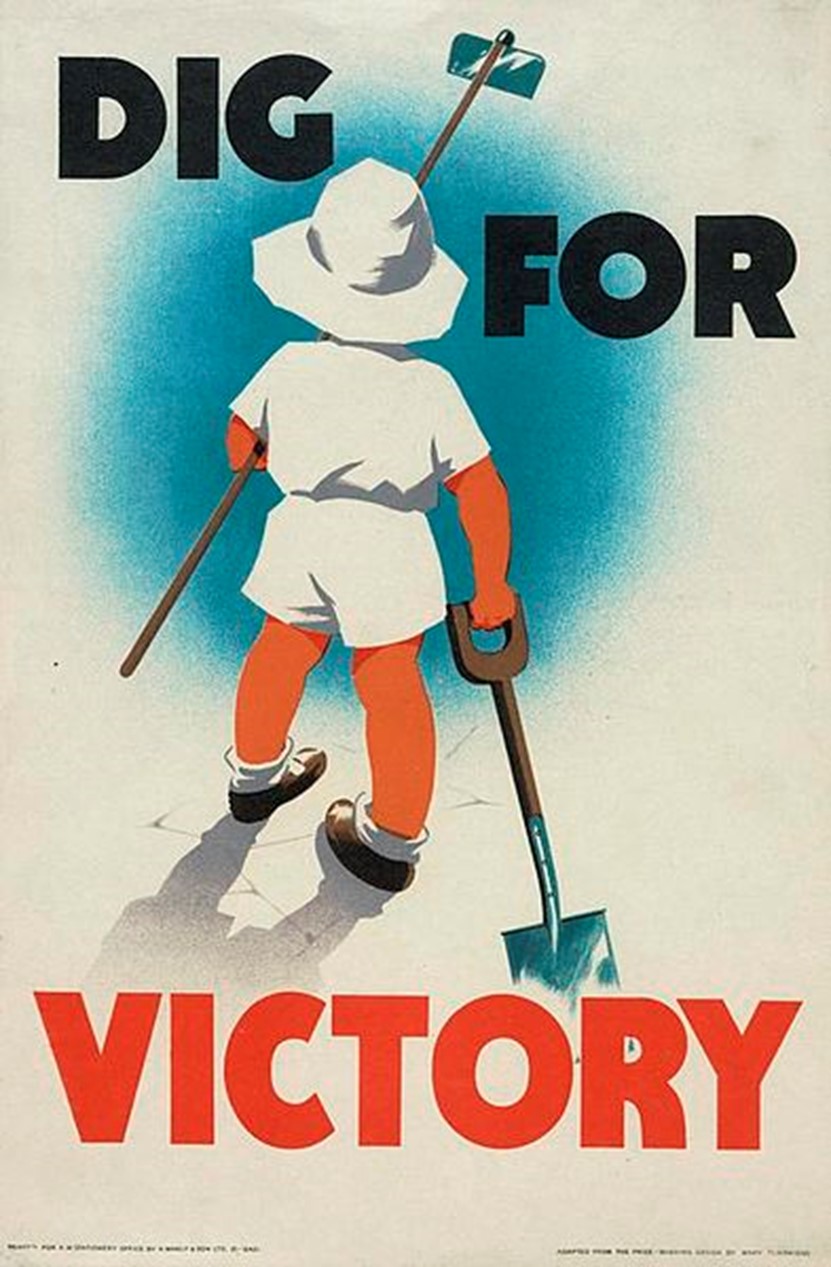

A food emergency is likely to be global or Europe-wide, and it’s poignant that in theory, Britain should be relatively well placed to handle it. Climate change here can be adapted to, as shown by the research I commissioned on adaptive cultivation methods and crops. Growing through Climate Change is now available in an edition focussed on Wales, and one for South West England. The UK has a large acreage of productive farmland, and still relatively high GDP per head, enabling us to buy food even if prices rocket.

An obvious step in a major food emergency would be for the UK Government to require farmers to slaughter most of their livestock, freeing up large supplies of wheat for human consumption. We only have to look back to World War II for a role model of how food rationing actually improved nutrition and health. Do we currently have a Government with the courage and capacity to take drastic action if the need arises?