Powerful insights from a woodland intensive

You may think it’s obvious that doctors have feelings, like anyone else. What I’ve learned from leading resilience programmes with doctors is that it’s far trickier. Most doctors like to believe they’re superhuman, at least at work. And what’s worse, most of us as patients want them to be superhuman.

This blog is a debrief on a recent resilience intensive which I co-led at Hazel Hill Wood. This was a quite different group from the previous one, with 25-27 year old junior hospital doctors (click here for the blog). This time our participants were in middle to senior positions in large London hospitals, age 29 to 50, up to Consultant level.

We all know that the NHS is chronically overloaded, and this is impacting staff at all levels. The numbers of NHS staff leaving or burning out is well up on a few years ago. One crumb of comfort is that this issue is becoming a priority within the NHS, and I’m seeing a rising interest in our programmes.

The idea of taking hospital doctors off to a one-night residential in a wood to help raise their resilience is still a novel one. The Westminster Centre for Resilience have been the catalysts in bringing these groups to Hazel Hill Wood. They have worked with medical professionals for several years, in London, but concluded that the power of a Nature immersion programme was needed to make further progress.

Those wanting hard medical research as to why Nature contact can make such a difference can now find it: for example, see my blog on the book Your Brain on Nature written by two doctors at Harvard Medical School.

Our programme at Hazel Hill Wood had broadly the same sequence as the previous one for junior doctors:

- Physical conservation activities and reflective time in the wood to help participants de-stress, connect with each other, and open to new insights.

- A campfire sharing circle after supper, where people could share their stresses and find support.

- On the the second day, a session on practical resilience skills using parallels with the woodland ecosystem from my Seven Seeds model, plus some from mindfulness, and some exploring the neurophysiology of stress management.

- Time to practice applying these methods to work situations, and to share with others how to sustain positive change.

At the end of the junior doctors programme, I was left deeply frustrated with a health system which exhausts its staff in delivering the outstanding care most patients receive. At the end of this programme, I came away more hopeful. These middle and senior level staff gained a lot of insights into ways to make work more sustainable for themselves and their teams.

The unremitting pressures on health professionals won’t disappear, but one big aha was realising that repeated minor changes, which take minutes or less, could have a big cumulative effect. Here are a few examples:

- Use time you have to spend walking along corridors or scrubbing up to take a few deep breaths to de-stress yourself

- Taking a minute or two for a team to check in, and say briefly how they’re feeling, can have a big uplift in everyone’s morale

- Even a few words of appreciation help hugely, and can create an upward spiral in mood

- There are better ways to handle angry patients and cynical colleagues – you can change your habitual self-blaming response

- Self-care is vital, and needs short actions taken repeatedly, such as writing yourself a few lines of appreciation before bedtime each day

Any doctor who gets to these levels in the NHS has to be smart, competent and resilient. Our four-hour conversation around a campfire in the dark, with owls calling around us, was a slow and deep unpacking of the problems and antidotes. To be part of this was humbling, moving, and a real privilege for me.

Gradually, these senior professionals opened up about how hard it is to open up. To show any vulnerability to colleagues leaves you liable to judgement and gossip. To show any uncertainties to patients alarms them. And nearly everyone said it was hard to talk about work to family or friends: ‘non-medics just don’t understand.’

Most of these doctors relied on a couple of close colleagues to share feelings and get support, but they could see this wasn’t enough. The idea of a phone helpline, someone medically trained and able to mentor you right after a difficult incident, could help a lot. And we explored ways to share some feelings, positive and difficult, with colleagues in general, and how this could help everyone.

A key member of the facilitation team was Professor David Peters, who set up the Westminster Centre for Resilience, trained as a doctor, and has been a medical professional for over forty years. He said, “doctors need to admit that the work is emotional.” He spoke about mirror neurons, which mean that doctors will absorb some of the distress of patients and stress of colleagues. His physiological explanations of how breathwork, mindfulness, and time in Nature can help, really enabled our doctors to understand and accept new techniques.

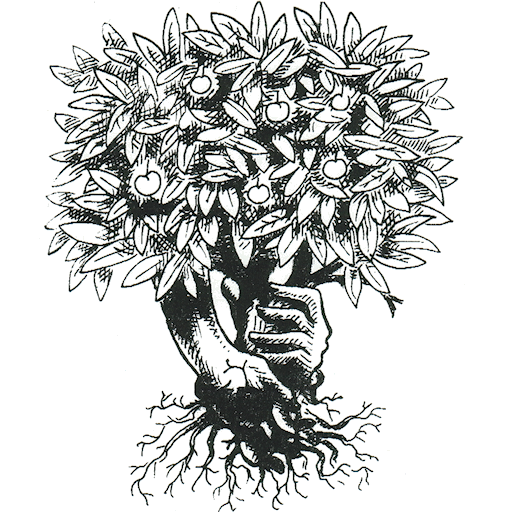

For example, early on I invited each doctor to connect with a tree, For me, it was hugely rewarding to see that my ecosystem model of resilience (details here) was of practical benefit. For example, early on I invited each doctor to connect with a tree, and use this contact to assess the balance of their own roots, trunk and branches (resources, processes and outputs). The simple physical experience of this analogy worked well, and they referred back to it repeatedly later in the programme.

The participants’ evaluation of benefits from this programme was highly positive, and Westminster Centre will continue monitoring to see how progress is sustained. Meanwhile Hazel Hill Trust, the charity which runs Hazel Hill Wood, is exploring other clients in the health sector who want to try this innovative approach to resilience.

For more information, see:

Hazel Hill Wood website: www.hazelhill.org.uk

Alan Heeks’ resilience website: www.naturalhappiness.net